Cities around the Great Lakes region are trying to make transportation cheaper for riders and more environmentally friendly by expanding their public transit networks. Two modes that are often pitted against each other are light rail and bus rapid transit (BRT). While not every BRT line meets the same standards, in general, they have been upgraded for higher capacity and speed, although they have fewer stations. Some of these reforms include giving buses a dedicated right-of-way, having riders pay their fare at the station, and elevating stations. A few examples in the Great Lakes include the Red and Orange Lines in Minneapolis-St. Paul or the HealthLine in Cleveland.

But even if it is faster than a normal bus, would you actually ride it? What do you think of when you think of the bus?

Maybe you take the bus every day to get to work. Even if you do, you might view it as more of a necessity than a pleasure. Maybe your bus stop is just a sign on a pole, with nowhere to sit and no shelter from inclement weather. If you have a physical disability, or if your knees just aren’t what they once were, you might struggle to step up into the bus. Once you get on, your bus might be slowed to a crawl by traffic jams.

By contrast, a trip on light rail seems futuristic and comfortable. These trains are more likely to have a dedicated right-of-way, so they worry less about running into other traffic. The tracks built into the ground give a sense of security, as opposed to a bus route that, it seems, city leaders could eliminate on a whim. Plus, as two people I spoke with for this article put it, trains are “sexy.” For many, a sleek train is just cooler than a boring bus.

But how much of this is about perception, not transit quality? What if there was a way to make the boring old bus faster and more efficient?

Enrique Peñalosa, the former mayor of Bogotá, Colombia, famously said, “An advanced city is not one where even the poor use cars, but rather one where even the rich use public transport.” Bogotá, the national capital, has a population comparable to New York City and is about as dense as Washington, DC. But while both of those US cities have rail systems, Bogotá’s world-renowned network relies on buses.

Bogotá makes heavy use of BRT. Bogotá and other South American cities, such as Curitiba, Brazil, host some of the most famous BRT lines. But many cities around the Great Lakes region have been experimenting with this technology, which is often pitted against light rail in transit planning debates.

METRO Blue Line Grand Opening. (Photo Credit: David R. Gonzalez/Minnesota Department of Transportation)

In general, both BRT and light rail sit in the middle ground between a regular bus and the highest-capacity “heavy rail” systems, like the Toronto subway or the Chicago L.

“If it ends up being something that we need a lot of capacity for, then we’ll say, OK, we’ve got to go heavy rail, let’s propose a subway here. Or if it’s something more intermediate, could be light rail, or if it’s something a little less, could be BRT,” said Eric Chu, head of transportation planning at the Toronto Transit Commission.

For example, in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, the local transit agency is expanding both light rail and BRT service. Cleveland also has both light rail and BRT. Toronto has light rail, and Milwaukee, Madison, Detroit and Winnipeg all have BRT lines.

It is also important to distinguish streetcars from light rail, which is sometimes known as light rail transit (LRT). While they often look like light rail, streetcars, such as Detroit’s QLINE and the Hop in Milwaukee, are more likely to operate in mixed traffic, like regular buses do.

When building BRT, “you would definitely want corridors that have demand that is a little higher than for regular bus,” said Daniel Rodríguez, professor of city planning at the University of California-Berkeley. However, not all systems are the same. “A ‘heavier’ BRT looks more like light rail, a ‘lighter’ BRT would look more like a regular bus.”

A public bus operated by the Detroit Department of Transportation (DDOT) drives passengers down Woodward Avenue on Wed. May 7, 2025. (Photo Credit: Donté Smith/Great Lakes Now)

One difference between Latin American BRT systems and those in the United States was in their variety.

“The US implementation of BRT was much more locally designed and locally crafted, and it kind of filled all the spaces between bus and rail,” said Rodríguez.

David Locher is manager of enhanced transit for the Milwaukee County Transit System. When planning Milwaukee’s East-West BRT line, he said, “we took an existing [bus] line, we took the busiest part of that existing line, and we said, OK, what’s also the most congested corridor?”

In comparison to BRT, “often, light rail moves towards higher ridership corridors or potential ridership corridors,” said Nick Thompson, deputy general manager for capital programs at Metro Transit, which operates buses and light rail in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area.

“Try as you may, it’s hard to get a bus with more than 100 people on it,” said Joe Schwieterman, professor of public policy at DePaul University in Chicago.

While light rail generally has a higher capacity than BRT, a well-designed BRT line can still achieve impressive results, often for a lower cost than light rail.

“There’s no rationale from a technological perspective, from a policy perspective, why you would be choosing light rail in most situations,” said Baruch Feigenbaum, senior managing director for transportation policy at the Reason Foundation, a libertarian think tank. “There may be some isolated instances out there where demand is great enough that light rail makes sense, but most of those places are places that have built light rail. Some of those places are places that have built heavy rail.”

“Most US cities have not reached the point where they need to graduate from buses to something that requires more capital, that’s going to be more expensive to operate,” said Reece Martin, a self-described “public transit obsessive” who runs the YouTube channel RMTransit.

Passengers wait for the Detroit QLine streetcar at the Congress Street stop on Wed. May 7, 2025. (Photo Credit: Donté Smith/Great Lakes Now)

“Bus rapid transit is often looked at as a more cost-efficient approach, and in many ways it is,” said Joe Grengs, professor of urban planning at the University of Michigan. “On the other hand, for the services to be comparable, bus rapid transit really needs to be in dedicated lanes, meaning that they’re not mixing with traffic. That is a very difficult thing to achieve in the United States. It’s very difficult to take road space away from drivers.”

On the other hand, putting a successful BRT line right next to a crowded highway could entice people to switch.

“When you have a dedicated BRT line that’s next to a congested roadway, people can see the opportunity to switch. If that BRT lane is moving faster than the other lanes of traffic, people might consider switching,” said Orly Linovski, professor of city planning at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, where part of the BRT Blue Line runs on a dedicated transitway.

Another political challenge faced by BRT is perception. Above, I outlined some of the concrete reasons people are often put off by the bus, such as slow service. But in many North American cities, there is often a social stigma around the bus as well. Because our cities are, in general, primarily designed for cars, the bus is often associated with people who exist in the margins of society.

“There’s this idea or narrative in the U.S. that buses are for people who don’t have other options,” said Laurel Paget-Seekins, a transportation justice advocate at Public Advocates, a progressive nonprofit. “That’s not entirely true. But that’s an idea.”

According to Paget-Seekins, improving the quality of bus service, such as through BRT upgrades, could help with this stigma. “Part of the idea of bus rapid transit is to prioritize buses, and to, in a way, democratize the street. If you think about the street, curb-to-curb, as a space that belongs to everyone, that space is not democratically allocated now. Bus riders don’t get their share of the street. One of the things bus rapid transit does, by creating bus lanes, is to democratize the allocation of that public resource.”

Grengs, of the University of Michigan, has studied the best ways of getting around the Motor City.

“I did a study that evaluated the difference in reaching important destinations in the region, driving versus transit. Even the locations where transit is best fall way short of driving,” he said. “After decades of deliberately building metropolitan areas to accommodate cars, we live in a country where our transit service just cannot compete with driving cars.”

The METRO Red Line at Ceder Grove Transit Station. (Photo Credit: Eric Wheeler/Metro Transit)

In some ways, the promise of BRT — fast, consistent service and a pleasant rider experience — is just about building better transit in general. In that sense, a “light” BRT line that doesn’t meet international standards can still improve a transit network. And while it’s harder to do ribbon-cuttings and photo ops, improving the frequency and reliability of the regular old bus can be a big help to city residents.

“It’s kind of the vegetables of urbanism, but just having buses that run frequently are infinitely more useful to people and infinitely better transportation than a train that might exist, but only runs every half hour,” said Martin, of RMTransit. “A bus that’s actually convenient, where you go on Google Maps and you go, hey, there’s a bus here in 3 minutes, that’s something that regular people will actually use.”

Some argue that even in cases where BRT could meet demand from riders, there are other reasons why light rail could be a better option. Transit lines aren’t just for moving people: they can also affect the local housing market and the economy in general, especially when they’re paired with land use reforms that allow for denser development near transit stations. People who live closer to each other tend to emit fewer greenhouse gases, and some research indicates that increasing the supply of housing can help slow down rent increases.

Both potential residents and developers sometimes see a rail line as being more permanent than a bus route, and are therefore more willing to bet on its future by building or living nearby.

“Another pivotal advantage of rail is the signal it sends to developers that the transit service is high-quality and permanent,” said Schwieterman, the public policy professor. “That signal is weaker when you merely build bus corridors.”

METRO Green Line Opening Day celebration at Target Field Station. (Photo Credit: Mike Doyle/Metro Transit)

However, not everyone shares this view. According to Feigenbaum, who studies transportation policy, the real driver of development is not light rail in particular, but zoning changes that allow for more density near stations.

“I have not seen any evidence that once the zoning is changed and a BRT line is put in, that in an equivalent corridor, somewhere else in the country that’s light rail, there was more investment put in,” he said.

Nick Thompson, of Minneapolis-St. Paul’s Metro Transit, said that his agency works with cities to encourage development around both light rail and BRT.

“We’re still seeing a lot of development around BRT, too, but not as much as LRT, so that could be a perception of the market,” he said.

In many ways, the debate over BRT and light rail comes down to perception.

“There’s an awful lot of people who don’t think that they would ever get on a bus who would have no problem riding rail,” said Megan Owens, the executive director of Transit Riders United, a Detroit-based advocacy group. “I don’t know how we break that other than to continually make the bus service better.”

It may be easier to change those perceptions than one might think. Vishnu Ravichandran, a friend of this reporter, works near an under-construction BRT station in Maplewood, Minnesota. He thought it was light rail until I pointed out that the Gold Line is actually BRT.

“The station looks a little like a rail station,” he said via text message. “I saw tracks that resembled railway tracks but looking back on it now, it just seemed like a line for buses.”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

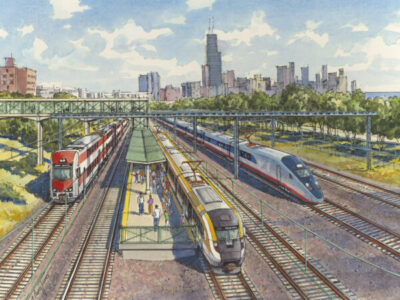

What would the Great Lakes region be like with bullet trains?

In Chicago, adapting electric buses to winter’s challenges

Featured image: The Detroit QLine streetcar prepares to pick up passengers at the Grand Circus stop on Wed. May 7, 2025. (Photo Credit: Donté Smith/Great Lakes Now)